Reviewed by Dawit Mesfin

“Was the Ethio-Eritrea Peace Accord of 2018 Aimed at Invading Tigray?”

“I was in Ethiopia frequently in the lead-up to this crisis to monitor refugee flows and progress toward peace for the Norway Foreign Ministry; and I watched with horror as what had seemed in 2018 like an opportunity to put an end to the feud between Eritrea and Tigray slipped away in 2019 and set the stage for the war that followed. It was like witnessing a train-wreck in slow motion – you knew where it was going but no one was putting on the brakes as they raced toward each other on a single track.”

Dan Connell

Dan Connell, believing in the Eritrean independence struggle, broadcast the freedom fighters’ experience as widely as he could in the hope that the world would begin to pay attention to what was going on, would learn from and support it. And it did.

He was so much into the liberation struggle he managed to attain a comprehensive understanding of EPLF’s internal structure during the armed struggle as well as post-independence Eritrea. Basically, he studied Eritrea for nearly three decades - starting in the mid-70s, when the freedom fighters were engaged in pitched battles against the Ethiopian troops.

That is why he said: “the Eritrean Revolution has defined me for most of my adult life. At times, this has entailed personal sacrifice. Also risk. But it has been an enormously enriching experience.” That was then; thirty years ago. What about now?

Dan Connell’s updated and reappraised book - ‘Against all Odds’ - describes Eritrea’s plunge into tyranny after the Badme War (1998-2000), the sullen ‘no-war / no peace’ years that ensued, and the optimism raised by a 2018 peace accord with Ethiopia and then shattered by another round of war in Nov 2020.

The Early Days

Connell’s visit to Ethiopia/Eritrea was rather accidental, according to his prologue in ‘Against All Odds’. He left the US in September 1975 to visit Africa. His aim was to study the diverse cultures and modern history of Africa.

He was so turned off by the Tanzanian and Mozambican bureaucracies he shifted his focus on Ethiopia instead. There he learned about the conflict in Eritrea.

Starting in 1976 he toured Eritrea more than fifteen times. Between 1976 and 1981, Connell reported on the conflict under five different names for a wide range of print and broadcast media in North America and Europe – BBC, VoA, Reuters, Associated Press, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Miami Herald, Time Magazine, The Guardian, The Financial Times, Le Monde, La Republica and more.

In the 80s, Connell continued to report on the Eritrean conflict and the chronic famine which was the outcome of the harsh conflict and recurring draughts. In 1991 he started to write ‘Against All Odds’.

‘Against All Odds’

Dan Connell is mostly remembered for his 1993 book which chronicled the epic liberation struggle in Eritrea. It was exciting to read ‘Against All Odds’ because it was written in the era Eritrea burst onto the international stage after a three decades long of armed struggle.

The book was his personal account of the Eritrean Revolution as he experienced it himself for sixteen years (before independence).

Noam Chomsky, the renowned American writer and author of many books, wrote: “Dan Connell’s vivid eyewitness portrayal and historical study lifts the veil on a remarkable popular liberation struggle that is too little known and understood. It is an inspiring story of courage, dedication, achievement and hope, with important lessons to teach.”

Who would forget the extraordinary account of ‘Inside Asmara’, the first chapter, when Col. Beshu, the commander of Ethiopian forces in Asmara who was trained by the Israeli counter-insurgency forces, was assassinated by urban guerrillas in front of ‘Bar Kebabi’ in Asmara?

Thirty years after the publication of ‘Against All Odds’, Connell revisits the past to appraise where Eritrea went wrong. What happened to all the courage, dedication, and achievement and hope the freedom fighters formed back then?

He writes:

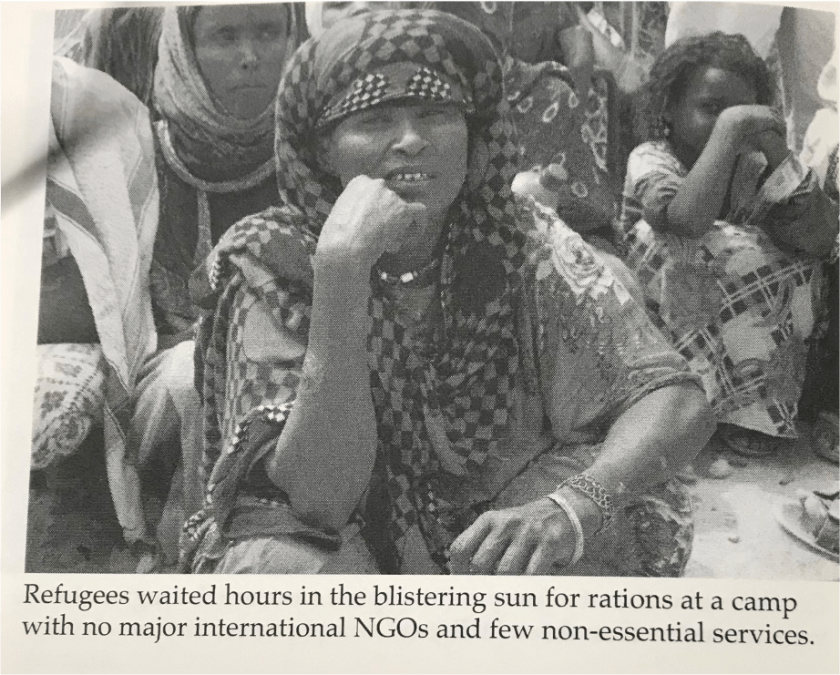

“The failure of the Eritrean government to signal any intent to reform despite a dead economy – apart from a narrow band of state-sponsored mining projects whose benefits accrued to the party – combined with the increased ability of people to get out more easily triggered a flood of new refugees. The numbers registering in Ethiopia from September 2018 through the start of 2020 hovered around 4,000 per month, higher than at any time before.”

The Man and his Writings

Connell followed events in the country closely as a journalist, analyst and eventually as an academic, writing hundreds of articles and papers about the country’s successful rejection of Ethiopian rule and its adoption of bold and creative approaches to the challenges of development and nation building.

Inspired by the Eritrean revolution, he wrote Rethinking Revolution: New Strategies for Democracy & Social Justice: The Experiences of Eritrea, South Africa, Palestine & Nicaragua (Red Sea Press, 2002)

In 2002, he prepared an Eritrea guidebook which was published by Eritrea’s Ministry of Information – a book that highlighted Eritrea’s achievements and contained special sections on the history, the land and the people of Eritrea. It was during that time (2001-2002) that Connell started registering serious reservations about the direction the country was taking.

In 2003, Connell published his “Taking on the Superpowers: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution (1976-83), vol. 1”; a year later, he published “Building a New Nation: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution (1984-2002), vol. 2.”

BTW, Dan Connell also published the 3rd edition of the Historical Dictionary of Eritrea which came out in 2019. It contains a chronology, an introduction, appendixes, and an extensive bibliography. Its dictionary section has hundreds of cross-referenced entries on important personalities, politics, economy, foreign relations, religion, and culture.

The Shift of Opinion

Connell, increasingly troubled by the repressive stance of the Isaias Afwerki government towards the press and political opposition, he found himself shifting from being a longstanding supporter to a critic.

He witnessed the unimaginable and sweeping changes in the post-war political situation in Eritrea have undermined the very democracy project that drew him into Eritrea for so long.

He chose to make that shift public at the African Studies Association meeting in Boston. He presented a paper, setting out the road he has travelled to arrive at his critical views.

Having reached a tipping point, in 2005, he published “Conversations with Eritrean Political Prisoners.” Connell managed to reproduce interviews with five prominent critics of Eritrea’s slide into one-party despotism - top government officials and liberation movement leaders - shortly before they disappeared into a secret prison. Eritreans living abroad have just marked the 20th anniversary of their disappearance on 18 Sep, 2021.

Connell still argues that the Eritrean experience was unique. He admires the integration of ethnic and religious minorities, the elevation of women’s status, the suppression of crime and economic corruption and more.

However, the country’s trajectory in post-independence Eritrea came as a shock to many, including Connell. Eritreans witnessed that power was concentrated within the executive branch of government; they also witnessed the setting up of an in-name-only parliament and judiciary. Critics, simply speaking, do not exist in Eritrea; not because the regime is beyond reproach, but there is no platform for criticism.

The Reappraisal

In this recently updated and reappraised book, Connell shows how the president managed to consolidate power - by justifying his extended stay in office due to the ‘fragile state of the nation’.

The pattern that unfolded within Eritrea was a giant step backward for the objectives, the values, and the vision that Connell chronicled in his news articles throughout the liberation struggle and that he so strongly argued for in his analytic writing in the post-independence period.

“What prompted you to update ‘Against All Odds’ instead of writing a new book?” I asked.

Connell replied by saying the following:

“Writing a new book is a major undertaking that would take years to do for me. As you know, I am working on a new book now, Eritrean Journeys, that will cover my experience as well as that of the refugees I’ve met over the years (both within Eritrea and afterward). Doing an update for Against All Odds, even a 65-page one (plus photos, a preface, and an appendix), was simply a different project. Given the urgency of addressing the current situation in the Tigray war and within Eritrea today, the idea of doing an update and reassessment seemed to me to make sense—and to do so quickly.”

Summarising his supplementary valuation, he said:

In retrospect, I know (and knew for many years) that Isaias was a cold, ruthless person obsessed with power and as I say in the Reappraisal, someone who held grudges for years.

I make a number of references to his character going back many years, though no detailed critique of him personally. I wanted here to focus on the arc of the country and its leadership. Isaias is a key part of this but not the only one, so I did not want to make this Reappraisal just about him. That bit will come with my next book. I have drafts of some now that include a story about my clash with him in the mid-80s over establishing Grassroots International to do aid and information work on Eritrea and other places.

In this, I refer to 1973 and the media and other signals of who he was and how he operated from the start. I just didn’t want to get deeply into this in Against All Odds where my main intent was to update the narrative and concentrate on Eritrea’s role in the Tigray War.

My evaluation of Isaias is that he has been a strategic whiz but has deep character flaws that have always been there, along with his ambition and authoritarian nature.

However, my approach to this is consistent with other projects I’ve done in the past. Each was prefaced by my essay “Enough! A critique of Eritrea’s post-liberation politics,” which I quote in the Reappraisal.

I do not want to sanitize or change what I wrote in 1993. I do not think it honest to do so. Instead, I have reappraised the movement and offered a mea culpa for my tunnel vision and for holding off on publicly voicing criticisms I was making behind closed doors in the 1990s. This is all part of my journey, as are other articles I did over the last decade.

Behind closed doors describes the whole Eritrean experience too well. I am not surprised Dan was caught up in the mesmerising spell of EPLF… albeit Isayas! The euphoria didn’t only cloud Eritreans but also onlookers.

The magic of the liberation created myth around the leadership which is taking decades to dispell.

Maxima culpa is the more appropriate thing to say, for the horror in Eritrea was a prelude to the coming genocide in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Better late than never, your self insight is appreciated and I hope it will give us a lesson not to get carried away.

In the first weeks of the war, as word of the Eritrean aggression was coming out, I was sent a video of Dan Connell discussing the war with Selam Kidane. I initially didn’t even want to watch being aware of his authorship of against all odds (but unaware of his later criticisms). The sender prevailed on me to watch it, that its not what I expected, so I watched and they were right, it wasn’t. It was a lone voice calling in the wilderness in those early days. Congratulations, Dan, on following your conscience

I beg to differ with Dan’s characterisation of Isaias as a “Strategic wiz” because he (Isaias) is a non-strategist evil man and that has been amply demonstrated over the years.

However, I accept he, on the face of it, looked and looks strategist because the people surrounding him have always been utterly weak and divided. Strategist can chain sentences to put their points of view across but Isaias can’t -even in his own language.