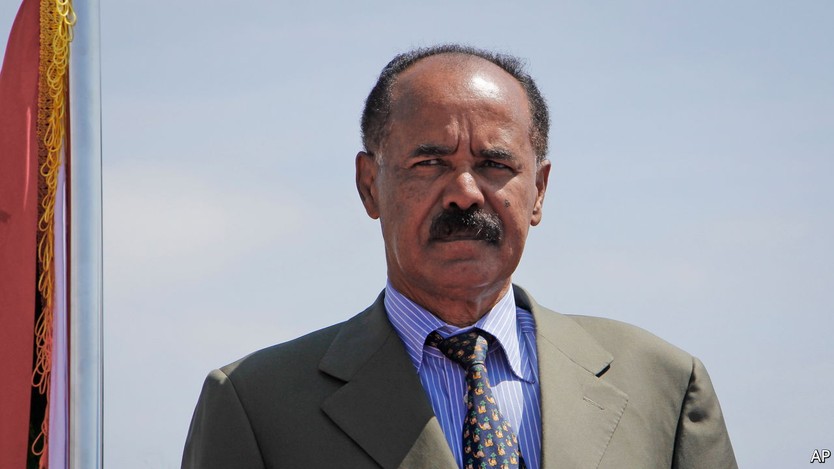

Sanctions should be reimposed on Issaias Afwerki’s regime

Source: The Economist

Dictators seldom improve with age or time in office. As they grow accustomed to untrammelled power, they forget why restraint is a virtue. As they punish truth-tellers, they hear more lies. After years of tyrannising their own people, they wonder if they can get away with bullying foreigners, too. Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un are not the only despots who menace their neighbours. Eritrea’s Issaias Afwerki is equally malign.

He is the only leader his country has known in three decades of independence. He has turned it into a hot, dusty prison camp. He has fought wars against two neighbours, stirred up trouble in several others and, in 2020, sent troops into Ethiopia’s civil war, where he is seen as the main obstacle to ending that bloody conflict. Restraining him would be a public good.

Little is known about life in Eritrea under Issaias. His regime allows no free press and keeps out foreigners, particularly journalists. Travelling incognito, The Economist recently gained a rare glimpse inside the secretive gulag state. [See below]

Our reporter found a country that has taken an even grimmer turn after 19 months of war. Shops are almost bare. In Asmara, the capital, cafés that once buzzed are now empty. Young people are afraid to leave home, in case they are press-ganged into the army—a horrific prospect.

Issaias rules by fear. Honest advice is unwelcome, much less criticism. Early in his rule soldiers complained that they had not been paid for two years and were unhappy that he wanted to withhold their wages for another four. He met them, heard their grievances, then locked up their leaders for 14 years. A few years later, when 15 senior members of his party signed a letter calling for democracy and human rights, Issaias tossed most of them into a secret prison. They have not been seen since.

Torture is common. Political prisoners—or even people who follow religions other than the four that are officially recognised—are locked in shipping containers in the desert sun, often without food or water. Some are subjected to the “helicopter” (lying facedown with their hands and feet tied together behind their backs) or “8” (being tied to a tree) for up to 48 hours.

Conscription lasts indefinitely: some Eritreans are discharged from the army only after 20 years or more of building roads, digging ditches or fighting. The young are barred from leaving the country. Thousands sneak across the border to Sudan and then on to claim asylum, often in Europe.

Eritrea also has a history of stirring up trouble with its neighbours by backing insurgents and proxies. In 1998 it fought a war with Ethiopia that cost perhaps 70,000 lives over a stretch of barren and almost uninhabited land. A decade later Issaias attacked tiny Djibouti to control the side of a disputed hill. He was also accused of arming al-Shabab, a militia in Somalia affiliated with al-Qaeda. These latter two actions provoked the un Security Council to impose an arms embargo on Eritrea in 2009 and financial sanctions on its political and military leaders.

In the past decade Eritrea has released Djiboutian prisoners of war, signed a peace deal with Ethiopia and appeared to be mending relations in the region. As a reward the un lifted sanctions in 2018. Yet Issaias’s good behaviour did not outlive the sanctions. He is widely blamed for having egged on Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s prime minister, to wage war on the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (tplf), an Ethiopian party-cum-rebel-group that Issaias has resented for decades. Eritrea is again thought to be supporting proxy forces in the region and it is building up forces on the borders of Tigray, where they threaten to wreck peace talks between Ethiopia and the tplf. “Everyone is beginning to arrive at the same conclusion: that if there is one spoiler in the region, it is Eritrea,” says a diplomat.

Stopping Issaias’s mischief-making will require firm action. America has already imposed financial sanctions on his army and ruling party. The un should follow this lead and reimpose an arms embargo on his regime. This would make it harder for him to threaten his neighbours directly, or to arm proxies. Yet this alone may not be enough. Regional powers should apply pressure. The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have long given Eritrea money and fuel in exchange for influence and military bases. They have an interest in stability; they should make this clear to their belligerent client. Finally, the region should plan for the day when Issaias, who has allowed no potential successor to emerge, dies or is toppled. Unlike tyrants, contingency plans can improve with time.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Inside Eritrea, Africa’s gulag state

Shops are bare, youngsters hide to avoid conscription

| ASMARA

In the corner of a quiet bar in Asmara, Eritrea’s capital, Mulugeta (not his real name) hatches a plan to escape. He has made contact with the people-smugglers who say they will arrange the crossing to Sudan. His older siblings in America have paid the fee. From Sudan, he will travel to Libya—and then to Europe. But his voice is hushed: in Eritrea a young man needs permission from the army to move freely. Mulugeta fears being conscripted and sent to fight in Ethiopia. He does not want to die in another country’s civil war.

Four years ago, young Eritreans caught a glimpse of a more hopeful future. Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia’s new prime minister, came to Asmara and embraced Issaias Afwerki, Eritrea’s dictator. The two signed a peace deal ending one of Africa’s longest-running conflicts, a bloody border war that had cost some 80,000 lives. It was fought most intensely about two decades ago for control of a few barren hillsides along the border with Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

By late 2020 Eritrea was back at war. This time, however, it is as an ally of the Ethiopian government in its ferocious campaign against the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (tplf), the party-cum-militia which runs Tigray. Once again Eritrean conscripts were ordered into Tigray, where they murdered, raped and ransacked towns on such a scale that Asmara’s streets nowadays thrum to the sound of stolen Ethiopian lorries.

Abiy, who at first denied that Eritrean troops were in Ethiopia, in March 2021 at last promised to have them withdrawn. Yet for more than a year his words proved hollow. Even after the Ethiopian army was routed from most of Tigray in June last year, large numbers of Eritrean troops remained. Last year they helped enforce a blockade of most food shipments to Tigray, which has pushed almost 1m people to the brink of starvation. Now change is afoot. In March Ethiopia agreed to a fragile truce with the tplf, raising hopes of an enduring peace in Tigray. More recently, Eritrean troops have pulled back towards the border (see map).

The course of Ethiopia’s civil war now depends to a great extent on when, and how, Eritrean troops leave Ethiopia. Issaias has nursed a grudge against the tplf since he fought alongside it to topple Ethiopia’s Marxist military dictatorship, which they did in 1991. Two years later Eritrea seceded from Ethiopia’s federation. Yet because Issaias has long believed that the tplf is bent on invading Eritrea and overthrowing him—a charge his government recently repeated—he is unlikely to withdraw his troops voluntarily without having first smashed the tplf.

Nor is he likely to negotiate. “We have consistently offered to engage Eritrea on how to de-escalate,” says a Western official involved in mediation between Abiy and the tplf. “They have not demonstrated a willingness to.” Some diplomats now worry that the tplf might indeed risk attacking northwards to Asmara if Issaias continues to refuse to join talks.

Behind all this the question arises: how much more can Issaias’s long-suffering citizens endure? To answer this a reporter for The Economist recently travelled to Eritrea, which normally bars foreign journalists. Most people interviewed were sceptical about winning the conflict against the tplf and blamed Issaias for dragging Eritrea into it. “We are tired of war,” says a priest. “Our children are dying for something that has no benefit for us.”

Cafés and bars once packed with young people are mostly empty. At the central market in Asmara piles of fruit are rotting in the stalls, while shelves in the shops are almost bare, save for what can be smuggled in from Sudan. With the outbreak of war the flow of contraband from Ethiopia abruptly stopped. Chemists are running low on medicine as basic as painkillers.

Even before the war, Eritrea’s system of indefinite national conscription had turned it into one of the world’s fastest-emptying countries. Few youngsters now leave their homes after dark for fear of being press-ganged. Military round-ups seem to be intensifying: a new training camp near Asmara opened in March. Every month hundreds of people flee across the border to Sudan. “Eritrea is like a giant prison,” says Mulugeta. Emigration drains the pool of potential conscripts, but it also makes resistance to Issaias’s rule—and his war—less likely.

Another question concerns the relationship between Abiy and Issaias. “Abiy wants the war to end, so Issaias is unhappy,” says an Eritrean working at a foreign embassy in Asmara. In January, the day after Abiy released some tplf leaders from prison, Issaias gave an interview in which he, in effect, claimed the right to intervene in Ethiopia to eliminate the tplf’s “troublemaking”. Since then, Abiy has made several visits to Asmara, perhaps to persuade Issaias not to undermine the truce. “So long as Issaias continues to meddle in Ethiopia’s domestic affairs, peace is unlikely,” warns an Ethiopian diplomat.

One Eritrean aim may be to block Tigrayan forces from reaching the border with Sudan, which they could use to bring in supplies. “If the tplf gets access, that means Eritrea’s security will be compromised,” says a soldier in Asmara. This also rattles officials in Amhara, a region to the south of Tigray, whose forces are battling to control territory along Sudan’s border that they seized at the start of the war. Amhara’s commanders have drawn close to their counterparts in Eritrea, who have hosted and trained thousands of Amhara militiamen. In the past week Abiy’s government has arrested thousands of critics and militia leaders in Amhara, perhaps to reduce the risk of that region becoming a threat to the federal government.

Hopes for peace are still alive. Tigrayan and Ethiopian commanders are in regular touch. Hundreds of aid lorries are being let into Tigray, though not yet enough of them. This week the tplf freed thousands of prisoners of war. Yet both sides are also preparing for another round of fighting. On May 2nd the tplf said it expected a new offensive from Eritrea. A week later Ethiopian officials accused the tplf of attacking Eritrean forces at Rama and Badme, the very site of the battle that sparked the border war in 1998. A single misstep could yet again lead to calamity.

Excellent peace. The world needs to follow the American example and impose sanctions on Eritrea without delay in order to prevent another war in the region.

For this reckless man, war and killings are just games that he cannot resist fuelled by his addiction to nightly bottles of Whiskey.

The article in some ways makes it clear that there cannot be peace in the Horn of Africa while Isaias is in power. That is absolutely correct and has been the case for the last 31 years since this madman came to power in the name of freedom.

The two things Isaias understand are; force and money.